Community Data 101 - Naming what we want to know, finding ways to use visual language to share our findings.

Description

As an integrated component within ongoing learning/classes, learners identify and generate questions about topics/issues of interest, ( including but surely not limited to housing, rents, utilities, food prices, jobs they have had, jobs they have, access to health care, immigration) as an initial piece of generating data to be used as learners see fit.

Using simple representations (use of color, stick figures, simple illustrations), they develop visual data as a means of entering into the processes of using spoken and written English to decode, understand and generate their own more complex data representations (increasing use of English language) over time. The process assumes that adults have understandings of and experiences with challenges in their communities but might not yet have the language skills to describe them, advocate for change or share analyses in English. It is intended to support learners as they gain confidence in using English so that they can develop both English language and literacy strengths in their ongoing work of speaking data and using it in support of advocacy of self and others.

Activity Goals

These activities suggest a process that can be used iteratively, can be repeated, changed and expanded as learners become familiar with ways of generating and understanding data pertaining to issues and topics of interest in English. It’s designed for very basic level ESOL classes (with minimal opportunities for bilingual or translanguaging processes [because of lack of shared languages or access to interpreters]). These processes can be adapted and altered for more or less fluent speakers. Again, the assumption is that adults understand the world they live in, its challenges and joys; they may need, however, to build their abilities to identify topics, generate data that enables them to address problems – or to celebrate achievements – in ways that ultimately increase their fluency as data speakers.

The activities suggested here include

- Asking questions to generate data through naming issues and topics of interest and importance

- Surveying others, interviewing neighbors, co-workers, friends, family about topics of interest

- Understanding various forms of infographics

- Using visuals to represent data, including:

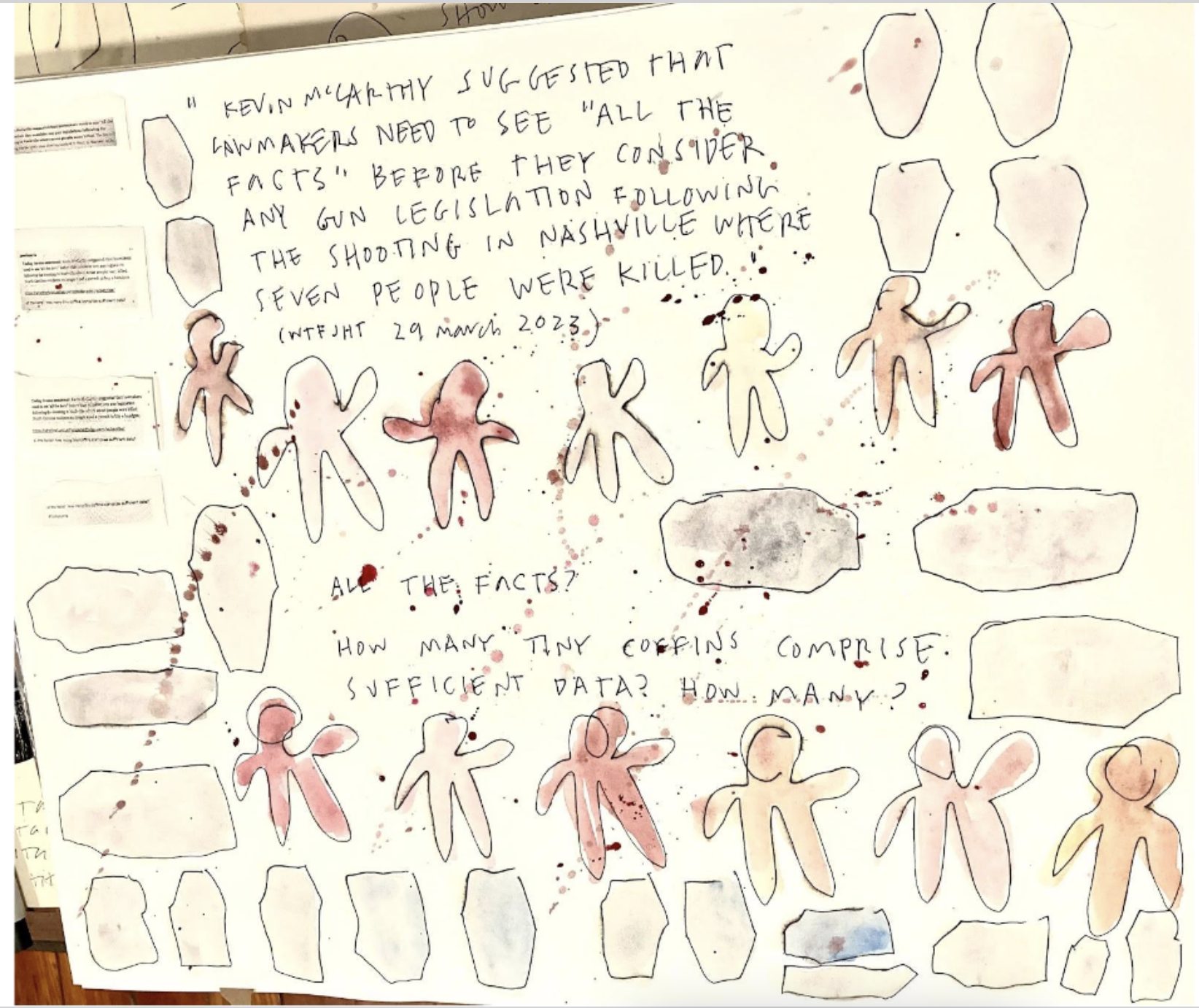

Problem-posing codes to elicit responses, generate discussion, critical thought and action.

Pre-existing infographics

Visual data representations generated by learners.

Maps, floor plans, directories

Key Objectives

UD.2 Identify types of data - Identify different types of data in everyday life, including the value of 'street data'

quick example: Learners take their phones for a walk around the block. What traffic signs do they notice? Graffiti? Trash bins? Trash? Bus stops? Parking spaces?

What do people notice? Compile/share the photos so that people can see

- what each other noticed

- any patterns in what was photographed

- problem areas?

- other things that stand out.

Facilitator can then develop a range of language and data language activites using these photos as catalysts.

- comparatives

- simple past tense (we noticed, we saw, there was, there were)

UD.6 Identify a need for data - Identify a need for data in their own communities and create an action plan to find or collect the data

quick example: We noticed that there was a lot of trash on the street, but only two trash bins within a two-block radius. Our photos might serve as data to justify the need to ask the city to install another bin or two. (information = there are two bins; data = two bins don’t contain all the trash). The city might pay attention to the evidence we present – the data is clear that we need more trash bins

SD.1 Ask good questions - Practice asking good questions (yes/no, wh-questions) that help learners clarify understanding of a data set and promotes curiosity

SD.2 Use the language of discovery - Use language of discovery, such as language for sorting, categorizing, naming, doubting, etc.

quick example: We noticed .. . We saw many ... There were ...

SD.5 Use language for interpreting data and data visuals - Use language for interpreting data and data visuals, such as language for comparing/contrasting, language for expressing change over time, language for making predictions

SD.6 Use language for respectful dialogue - Use language that demonstrates respect for different interpretations about data

quick example: Drafting a letter to a city councilor, preparing a phone script, inviting a local official to tour the neighborhood to see first hard what the issue is

PD.5 Play with different kinds of data visuals - Strengthen data interpretation skills by looking at the way different visuals changes our interpretation of the same data

quick example: Share a range of data infographics with learners to see what they already know/recognize about that form of communication; invite them to develop basic infographics about foods they like/dislike, movie genres, things they like to do, things they want to express as infographics

DS.1 Define data-storytelling - Explain how we tell stories with data – with numbers, words, dates, pictures, art, etc. -- and why data-storytelling can empower communities

DS.2 Adapt story-telling approach based on context, purpose, and audience - Adapt the way we talk with others about data – such as the choice of language, use of humor,

metaphor, personal stories, or technical words -- based on context, purpose, and audience

DS.3 Promote data-storytelling in your community - Identify 3 strategies for promoting data-storytelling in our own communities, in places and to audiences we want to reach

Student Work

Steps

1. Regular pattern of warm up/check in questions

As a regular and ongoing part of classes, learners check in about issues of concern. This might happen daily, and/or the facilitator might devote one or two sessions at the beginning of each unit/week/module – however s/he/they choose to allocate time.

To begin, the facilitator might offer this prompt: “I’m thinking about. [x] and wondering if this is something that interests other people.” The first [x] could be, “I’m thinking about the cold/hot weather and how people are keeping themselves warm/cool,” as part of a process of generating vocabulary and data about the sorts of utilities people have – gas, electric, included in rent, if people are unhoused are there warming/cooling shelters in the area?

This is part and parcel of a participatory approach to language and literacy learning, integrating issues affecting communities, addressing questions we have and establishing information about our contexts in order to then compare, contrast, ask, challenge and act. Language and literacy specifically emerge from the content and context of issues raised by learners. In addition to language elements (e.g. asking Wh questions, using simple past tense verbs to describe activity, generating vocabulary around a given topic), an approach incorporating data also pays attention to data as, initially, information that then become data to inform action through learners’ use of that data to provide evidence of a problem, a situation, a tendency, a trend.

2. Establishing vocabulary

- visual symbols – inviting learners to draw on the board, for example, stick figures representing people in the class, friends they know, people they like.

- use of templates (see, for example

- tactile alternatives:

- use of post-it notes to build bar graphs (see PCL guide, p. 26)

(also see PCL guide, p.17 for another way of using post-it notes to build information) ,

- Cuisenaire rods to represent numbers/objects/people

3. Ideas for action: working from data gathered, learners may choose an issue to pursue in order to understand and address root causes (e.g. brownfields, pollution), including identifying sources of more information, ways of generating data relevant to the topic at hand and then ways to use that data – share with other classes, contact people with power to make decisions, changes, educate others in the community, etc.

Downloadable files - exemplars to get started (if useful can be downloaded as PDFs and used as links within the site).

Health care: https://docs.google.com/document/d/11yUJgqxAA7Bb--P-RYymBRogsHqpSc6k/edit

Who lives where? https://docs.google.com/document/d/1G1mcCigRmBz26O957W6BTF8SGrNiwJoF/edit

Neighborhood worksheet https://docs.google.com/document/d/1gkYLMftlWJo2U9EJuiBt_g_G77b2NexQ/edit

– from Making Connections: Literacy and EAL from a Feminist Perspective (Toronto: CCLOW, 1996)

This worksheet is problematic in its descriptions of people of different ethnicities; it could be presented as is, inviting comments, feedback and pushback about ways in which people are represented. It could serve as an example of ways in which people are perceived, and how those perceptions bring benefit or harm. It could also be adapted by the facilitator and/or group participants to reflect the sorts of questions the group wants to ask, the people and activities they want to identify and examine.

Resources

On this site: community mapping: https://www.communicativejustice.com/activities-menu/community-mapping

into the box, out of the box: grids, graphs and ESL literacy – Janet Isserlis and Heide Spruck Wrigley

https://www.powershow.com/view/afda6-Nzc4Z/into_the_box_out_of_the_box_grids_graphs_and_ESL_literacy_powerpoint_ppt_presentation (retrieved 28 May, 2024).

Suggestions for using language presented in grids; these grids can be translated into visual representations as part of a concurrent process of building language, literacy and speaking data.

Providence Community Library Volunteer Support Guide

https://literacyresourcesri.org/pclmanual.isserlis.pdf (retrieved 28 May, 2024)

https://literacyresourcesri.org/pclmanual.isserlis.pdf (see section on grids pp. 9-10, 14 - 15)